Summary

Tarantula anatomy is the key to understanding their care, behavior, and survival strategies. This guide covers the external body parts such as prosoma, opisthosoma, fangs, spinnerets, pedipalps, sensory hairs, and urticating hairs, as well as internal systems including digestion, circulation, and respiration. Learn how venom works, why males and females differ, and why the molting process is one of the most dangerous times in a tarantula’s life. With practical examples and clear explanations, this article helps keepers recognize normal behavior, avoid common mistakes, and appreciate the fascinating biology of these alien-looking predators. Whether you are a beginner or an experienced keeper, understanding tarantula anatomy will make you a more confident and knowledgeable caretaker.

Introduction: Why Anatomy Matters

Understanding tarantula anatomy is key to providing proper care. Knowing how their bodies function helps you interpret behavior, spot problems, and appreciate just how extraordinary (and right-out alien 👽) these creatures are. Anatomy isn’t just for scientists or breeders. By learning about their body structure, you also gain a deeper appreciation for these animals that look so alien yet follow their own clear biological logic.

External Anatomy

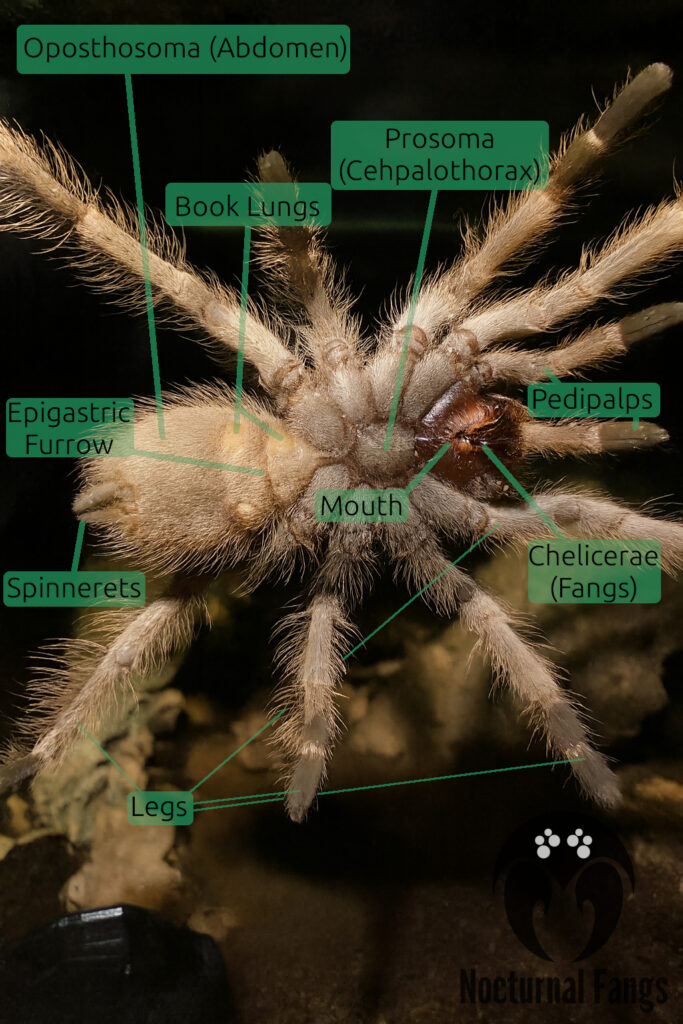

Prosoma (Cephalothorax)

The front part of a tarantula is called the prosoma, also known as the cephalothorax. This section contains the eyes, mouthparts, fangs, and legs. It is protected by a hard carapace, which acts like a shield. The prosoma is the control center of the spider, where all the main functions such as movement and feeding are coordinated. The small dent in the center of a tarantula’s carapace is called the fovea, and it serves as a point where internal muscles attach to help move the legs and control body functions.

Opisthosoma (Abdomen)

The back section of the body is called the opisthosoma, or abdomen. It is softer and more flexible than the prosoma. Inside, it houses many vital organs including parts of the digestive system, reproductive organs, and respiratory structures. The spinnerets, which produce silk, are located here too. Because the abdomen is delicate, injuries to this part can be life-threatening.

Eyes

Tarantulas have eight eyes, arranged in a small cluster on the front of the prosoma. Their eyesight is surprisingly poor. They can detect light and motion but cannot form detailed images. This is why tarantulas rely more on vibrations and touch than on vision. In contrast to tarantulas, spiders such as jumping spiders (e.g. Phidippus sp.) or wolf spiders (Lycosidae) have excellent eyesight.

Fangs (Chelicerae)

The fangs are among the most iconic features. Connected to venom glands, they are used to inject venom into prey. The fangs are strong enough to pierce insect exoskeletons, and in some larger species, even mammalian skin. They fold back under the body when not in use and swing forward when the spider strikes. The fangs are also the feature that separate tarantulas (infraorder Mygalomorphae) from true spiders (infraorder Araneomorphae). The fangs of tarantulas point straight down and operate in a parallel motion, while the fangs of true spiders cross each other in a pinching motion.

Spinnerets

At the rear end of the abdomen are the spinnerets, small finger-like appendages that release silk. Tarantulas don’t weave webs like orb-weavers, but they use silk for lining burrows, securing molting mats, and anchoring themselves. Silk is also used to wrap prey or create draglines for stability when climbing.

Legs and Pedipalps

Tarantulas have eight legs, each divided into multiple segments. At the tips are small claws (tarsal claws) that allow them to grip surfaces. In addition, tarantulas have pedipalps, appendages that are shorter than the legs by one segment. Pedipalps are used for handling food, sensing the environment, and in males, reproduction. After their final molt, male pedipalps develop a bulbous structure at the tips, which functions as the organ for transferring sperm to the female during mating.

Sensory Hairs

This is where tarantulas shine. Their bodies and legs are covered with different types of hairs called setae. These aren’t just for looks (although sometimes, they add a striking contrast). Many of them are highly specialized sensory tools. Some hairs detect the slightest air currents, allowing tarantulas to sense movement from potential prey or predators. Others pick up ground vibrations, helping them “hear” footsteps in their environment. Certain hairs act like taste receptors, letting them gather chemical information about their surroundings. This sensitivity explains why a tarantula can react so quickly even though its eyesight is poor. In New World species, there is also a special set of setae called urticating hairs, used for defense.

Urticating Hairs

Found mainly on New World tarantulas, urticating hairs are barbed bristles located on the abdomen. When threatened, the tarantula uses its legs to flick these hairs into the air. If they contact skin or eyes, they cause irritation. Not all species have them, but for those that do, urticating hairs are often the first line of defense before using venom.

Urticating hairs have tiny barbed hooks along their shafts, which anchor into skin or mucous membranes and cause irritation once they are flicked off by the tarantula’s legs. There are several different types of urticating hairs (currently classified into seven groups), each varying slightly in shape and how they irritate predators.

Venom

Venom is central to how tarantulas subdue prey. The venom glands are located inside the chelicerae and deliver venom through the fangs. The potency of venom varies by species. New World tarantulas usually have milder venom, relying more on urticating hairs for defense. Old World tarantulas, which lack urticating hairs, tend to have stronger venom and display more defensive behavior. Venom breaks down prey tissue, making it easier to consume, and also deters predators. Tarantula venom is a complex mixture primarily made up of proteins and peptides, including neurotoxins that affect nerve and muscle function along with enzymes that help break down prey tissues, but for humans it is generally not medically significant and rarely dangerous, unless a person has a severe allergic reaction.

Sexual Organs and Mating

Sexual Organs

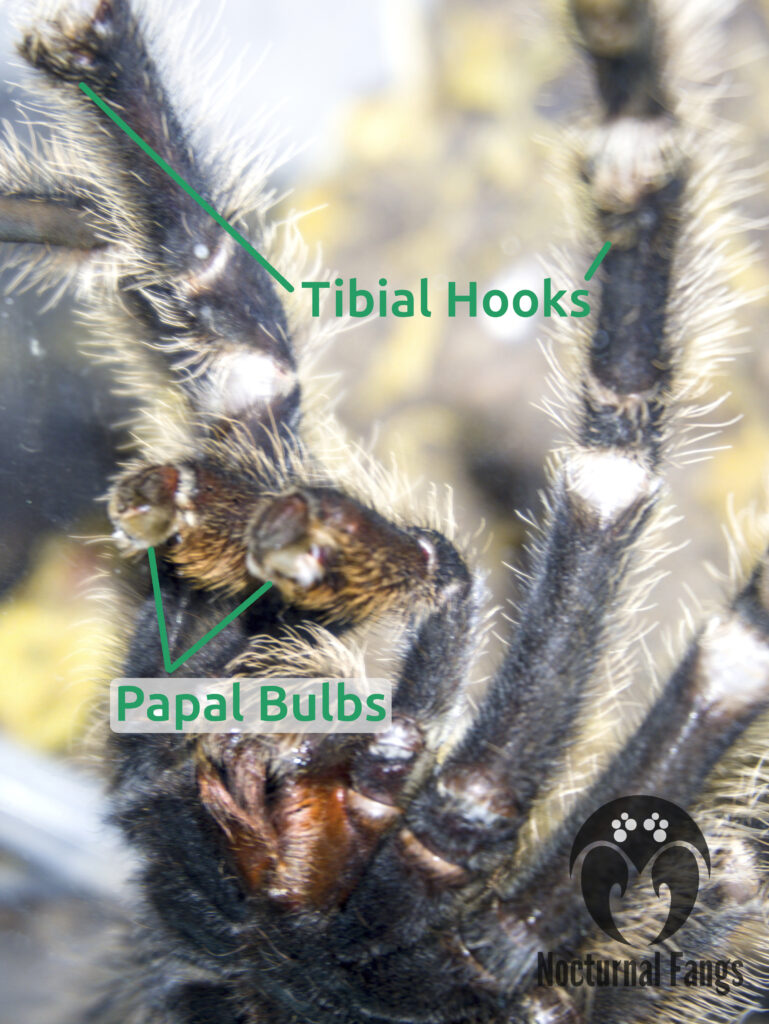

Males can be identified by their modified pedipalps, which look like small boxing gloves. These structures are used to transfer sperm to the female. Mature males of some species also develop tibial hooks on their front legs, used to hold back the female’s fangs during mating.

Females have spermathecae inside the abdomen, specialized organs where sperm is stored after mating. This allows them to fertilize eggs long after the mating has taken place. Because females can live much longer than males, they play the more critical role in reproduction.

As a general rule, different tarantula species cannot interbreed successfully because their sexual organs function as a key lock system. The male inserts his pedipalps into the female’s reproductive opening, but the shape, size, and internal structures of these organs vary between species. If the male’s embolus does not match the female’s spermathecal structures, mating cannot occur or sperm cannot be transferred correctly. This mechanical incompatibility helps maintain species boundaries and prevents hybridisation in the wild, even in areas where closely related species live side by side. However, some related tarantula species have sexual organs that are identical enough for the key lock system to match. In these cases, mating is physically possible and sperm transfer may succeed, which is why hybridisation can occur in captivity even when it would rarely happen in the wild. This is one of the reasons why accurate identification and responsible breeding are so important in the hobby.

The Mating Process

Mating involves a cautious dance. The male drums with his legs or pedipalps to signal to the female. If she accepts, he uses his tibial hooks to restrain her while transferring sperm with his pedipalps. The process is risky for the male, as the female may attack if she is not receptive or feed on the male after a successful mating. So for the male, a safe exit strategy can be a life-saver.

Internal Systems

Digestive System

Tarantulas practice external digestion. They inject digestive enzymes into prey, breaking it down into a liquid form. The tarantula’s digestive tract begins at the mouth, continues through the sucking stomach that pumps liquefied prey, and extends into the midgut and hindgut, where nutrients are absorbed and waste is prepared for excretion.

Circulatory System

Unlike mammals, tarantulas have an open circulatory system. Instead of blood, they have hemolymph, a blue-green fluid that carries nutrients and oxygen. The heart is a simple tube located along the dorsal side of the abdomen, pumping hemolymph throughout the body.

Respiratory System

Tarantulas breathe using book lungs, located in the abdomen. These consist of stacked layers of tissue that allow gas exchange. Air passes over the thin membranes, and oxygen diffuses into the hemolymph. This system works well for a sedentary predator that relies on ambush hunting rather than constant movement.

The Molting Process

Signs of an Upcoming Molt

Before molting, tarantulas often refuse food and may become more secretive. Although, I have personally observed my Nhandu tripepii taking food on one day, and then molting on the next. Sometimes they’re simply hungry beasts.

As a next sign, sometimes the abdomen can darken before a molt, and in some species, the bald patch where urticating hairs have been kicked off turns black. Lethargy is common as the spider prepares.

The Molting Event

When it is time, the tarantula flips onto its back or side, which often alarms new keepers who mistake it for death. But don’t be alarmed! The old exoskeleton splits, and the spider slowly pulls itself free. This process can take several hours. Disturbing a tarantula in the middle of a molt can be fatal, as even minor stress or movement may prevent it from successfully freeing itself from the old exoskeleton.

Risks of Molting

Molting is one of the most dangerous times in a tarantula’s life. If the tarantulas’ internal hydration is insufficient, the spider may struggle to shed its old exoskeleton. Limbs can become stuck, leading to injury or death. Providing the right environment reduces the risks, but even then, complications can occur.

The tarantula builds up its internal hydration gradually through food and access to fresh water, and last-minute misting of the enclosure during molting is more likely to cause stress or harm than to help.

After the Molt

Once free, the tarantula is extremely soft and vulnerable. The fangs are white and flexible. It can take several days to weeks (depending on the size of the tarantula, larger = longer) for the exoskeleton to harden fully. During this time, the tarantula should not be fed, as it cannot subdue prey safely.

Final Note

Tarantulas may look simple at first glance, but their anatomy is full of fascinating details. From sensory hairs that detect the slightest vibrations to complex reproductive organs and the dangerous molting process, every part of their body tells a story about survival. Understanding their anatomy not only helps you provide better care but also deepens your respect for these remarkable creatures.

Share this page

Enjoyed this page?

Top Utensils for Tarantula Owners: Items Every Keeper Should Have ReadyThe Right Tools The right tools make everything easier, safer, and less stressful for both you and your eight-legged companion.Having the proper utensils at hand means you can feed, clean, and manage your tarantula with confidence instead of panic. And trust me, when your old world tarantula suddenly decides to sprint up the tongs, you will appreciate every extra centimeter of length. The Essentials Feeding Tongs Feeding tongs are your best friend in this hobby. They keep your fingers out of striking distance and make feeding precise and clean. If you want to tong-feed your tarantula, plastic or wooden tongs are the safer choice, as tarantulas can and will sometimes bite into the tongs, and then a softer material is safer for your tarantulas fangs. Otherwise, go for long steel tongs. The longer the tongs, the more distance you have if your tarantula decides to run up them for a …